I pay $20 a month for the “privilege” of editing PDFs.

I understand there are other solutions that allow me to do this for free or at a fraction of the cost. I’ve tried many of these over the years and found that Adobe’s solution works best for me as a production tool. Having reached that conclusion, I don’t mind paying for it.

Lately, however, Adobe is making it hard for me to continue paying this fee. Every time I open the app, close the app, or even just move the mouse to the wrong portion of the screen, I am bombarded with advertisements.

First there is the startup ad. The first time I open the app, every day it seems, I’m presented with a popup detailing new features I might be interested in trying. I must engage with this ad, either positively or negatively, to proceed. It’s like a little toll my brain must pay to start working with PDFs.

(Note: I had already cleared the irritating popup which prompted this post yesterday before I had a chance to grab a screenshot. I knew that if I came back today I would get a new one, and bingo! there it was.)

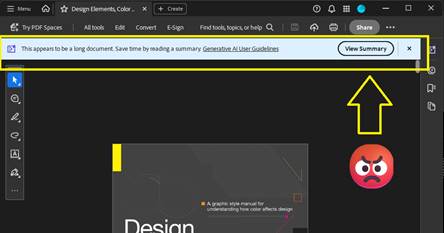

Thankfully I don’t need to close an ad like this every time I open the app for the rest of the day, but every time I open a document, I can be certain that another dialog recommending an AI summary will appear at the top of the screen. Let’s leave for another day the question of whether an AI summary is good for me, good for society, or whatever. Today I am irritated by the simple cognitive labor I have to do every time I open the app to work, to learn, or even just to read for fun. This dialog doesn’t obscure the document, but it consumes valuable real estate on my screen that I often can’t afford to give up. I have to think about it instead of what I’m reading.

After I’ve closed this dialog, I’m still not done dealing with distractions. If I make the mistake of moving the cursor to the bottom of the screen, another dialog appears. Not only does this dialog require another little jolt of cognitive labor to acknowledge and clear the distraction, it creates a slight disincentive against moving the cursor while reading. Worse, this one obscures a portion of the document for a second or more after I move the mouse away from the Hot Zone.

There’s something else about this dialog that drives me crazy. It activates a feature that is already controlled by a button at the top of the screen.

If I wanted to use this feature, I would click the brightly-colored button at the top of the screen! This drives me crazy because the application shouldn’t just execute a command on my behalf – especially not when it has recommended the feature on startup and then reminded me of its existence again and again with popups, dialogs, and colorful buttons. Don’t treat me like a stubborn child who needs to be forced to eat his vegetables. You say you don’t like it, Adobe asks, clearly the wise adult in this exchange, but have you even tried it?

What an insult.

On this computer I pay the bills. If I want to use the damned feature I’ll damn well click the damned button.

This insult poses a philosophical challenge as well. Ask yourself: when is it OK for a machine to operate itself? The deal we’ve made with machines is simple: operators should be the ones operating them. The machine should not operate itself unless the operator has instructed it to do so, or failing to perform an operation would risk injury. When it executes a command on its own, the resulting operation should be limited in scope and duration.

Perhaps a car offers some good analogies. In my car, the headlights turn on automatically when it gets dark because I’ve turned a switch—that is, issued a command—for them to operate that way. If I don’t turn the switch, they don’t turn on. The radio doesn’t randomly change channels to introduce me to new stations (yet). It doesn’t turn on at all unless I press the button. The engine doesn’t change to Eco Mode automatically when I cross the border into a new state. The things that do operate without my explicit command, such as the automatic door locks, do so because the risks associated with error are grave. If I don’t lock the door, it may open in a crash. You can imagine the consequences. I’m willing to hand over a little piece of my autonomy to the machine here.

Does this example of remote execution, this magic AI Assistant dialog, pass that test?

In my most uncharitable moods (like the one shaping this blog post) I think about how failing to click the “Ask AI Assistant” button threatens the careers of all the managers who are responsible for driving user adoption of AI at Adobe. I suspect that Number of Impressions—that is, eyeballs on the AI Assistant feature—is a KPI they can boost by displaying this dialog at the bottom of the screen when I move the mouse down there. When I’m in these dark moods I think that’s a dirty trick to pull on me. It’s especially low down when I’ve been kind enough to allow you to reach into my bank account and automatically withdraw $19.99 every month.

Believe it or not, we’re not done with adverts yet. After capturing the screenshots for this post, I clicked the OS window control to exit the application and close the window. To my amazement, the popup below appeared because I tried to exit without saving the document. Unlike the magic AI Assistant dialog, this could have been helpful! Alas. Rather than simply prompting me to save my changes, some manager at Adobe thought this would be another fantastic opportunity to sell me on a product feature by using dark patterns to drive my behavior. “Share for review” is bright and welcoming. Simply press Enter, it suggests, and turn on the light. And that WhatsApp logo is a big green light saying Go, Go, Go. “Save without sharing,” in contrast, is dark and foreboding, like the mouth of a cave—clearly a button for dullards and dimwits to press so they can stay in the Dark Ages.

Adobe isn’t alone here. Companies are taking these liberties too often. Just today, for example, Teams informed me when I started the app that there was a brand-new Copilot feature for me to try. I have to use Teams for work, so I spend a huge portion of my life—like it or not—staring at this application. I didn’t ask for this. I didn’t opt-in, and I can’t opt-out. My employer didn’t request the feature. But, nonetheless, there it is. A group of managers and devs forced me and millions of others to just live with this thing for eight or more hours per day and hundreds or thousands of dollars per year. And if we don’t care about the feature enough to click on it, they’ll find new ways to remind us that it’s there. I expect to see more popups, more nudges, brighter colors, shimmering icons, and other ruses from the big bag of user psychology tricks reminding me to Try Copilot! until the next KPI comes along that incentivizes Microsoft to arbitrarily and unilaterally change the app again and surface new features.

I see this happening every day in web apps, mobile apps, desktop apps, even the operating system itself. And before you swing your boots up into the stirrups of your high horse, I know I can use Linux to avoid most of this. I know I can use open source tools. I’ve used Linux as a daily driver on my personal machines since 2007, and I was using open source apps before that. It doesn’t matter. If I want to put food on my table I have to use these products controlled by Microsoft, Adobe, Apple, Google, Esri, Autodesk, and all the other companies who do these short-sighted, authoritarian things to try to alter my behavior and shape my daily existence. I can’t escape it, and neither can you.

But still, if Adobe could chill with the ads in Acrobat, even just a little bit, that would be nice. Until then, I’ll be over here closing popup adverts and keeping my cursor at the top of the window.

(Edit 2/11/2026: It pleases me immeasurably that this post seems to attract bots for SEO and Sales blogs trying to build an audience. Keep those likes coming. Irony is an artifact of the past. -CBC)