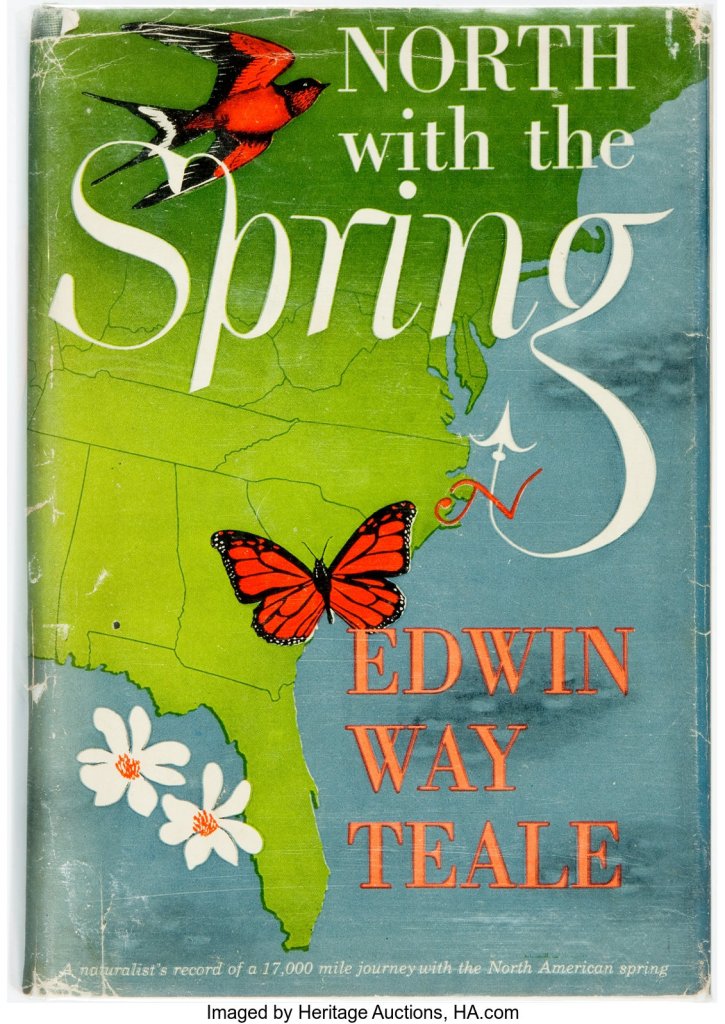

This week I am reading a classic naturalist’s work, Edwin Way Teale’s North With the Spring. This book is a must-read for anyone interested in Florida nature, but it should also be near the top of the list for anyone interested in how to be a naturalist. I picked up the book for the former purpose, but found myself enthralled by the latter. As an aside, this is one of the many ways I am enriched by breaking bread with the dead. I approach every book with an idea of where it will lead me, but I never end up in that place. Recent authors don’t often take me too far from the path I picture through the book, because we have shared many of the same experiences; going back only as far as fifty years, though, leads to wild and wonderful (and often chilling, challenging, and vexing) places.

I entered North with the Spring with a historian’s interest in how Teale thought of Florida in the 1940s. His idea was a compelling one: starting somewhere at the southern tip of Florida, he would follow the spring as it made its inexorable way to the wintry northland of New England. The book was popular in its day, and it has endured long enough in library stacks to have inspired others to retrace the path Teale took up the spine of the seaboard. I started the book with a research goal in mind, but I was immediately blown away by how Teale lived – and how different it is from the way so many of us live today. In contrast to our capsular civilization of AirPods, air conditioned and noise-canceling car interiors, tightly closed and carefully climate-controlled offices and apartments, Teale describes a way of living close to nature, constantly listening, looking, smelling, and most of all, responding.

Here is an example. “Each morning,” Teale wrote of the “pre-spring days” early in his journey, “we awoke while it was still, to the steady throbbing of fishing boats moving out among the Ten Thousand Islands of the Gulf.” Awakening further, Teale described a rush of sensory information. “With the earliest daylight,” he continued, “came the strident alarm-clock of the red-bellied woodpecker amid the palms outside our cabin….” Stepping outside into the cool February morning, Teale and his wife found “exciting new odors… all around us in the perfumed air of the dawn.”

I read this and think about my morning routine. I awaken in a sealed room. I do not hear birds. A ceiling fan whirrs overhead, quietly humming, while a tower fan drones on the other side of the room. The air conditioner hums through the ducts. Another fan spins noisily in the mint green heat exchanger supporting the air conditioner just below the bedroom window. In the bathroom I am beyond the sound of the fans, but still comfortably sealed within. I hear the nearest songbirds—a dueling Cardinal and Carolina Wren at this time of year– whistling their morning tunes from magnolia trees outside.

In contrast with Teale, I am distant from nature. I am almost hermetically sealed in my capsule.

While driving, Teale noticed plants along the roadway, changes in the communities of birds flocking overhead, minute details about the weather, small sounds, flashes of color. Taking a detour near Waycross, Georgia on the way down to the Everglades, he reported: “As we reached a stretch of swampy woodland, a storm of sound assailed our ears. All the trees were alive with blackbirds. Thousands swarmed among the branches, filled with the excitement of migration time. They were incessantly in motion, hopping, flying, alighting, combining their voices in a deafening clamor.”

I do not remember the last time I heard a “deafening clamor” of migrating birds outside my car window, and I suspect I am not alone. I look around and notice that the windows of every car around me are tightly sealed. We move through the world in capsular isolation. Meanwhile, Teale’s attention to the natural world was unaffected even by the clattering iron of rail travel. “If you come north by the train in midspring and have an ear for the swamp music of toads and frogs,” he explained, “you will become aware of something interesting. You seem to be running backward in time. As the spring becomes less and less advanced as you go north, you begin with the latest-appearing of the marsh-callers and progress backward to the earliest of the peepers.”

I am reading Teale’s account of the coming spring sunburnt and muscle-sore from a long paddle down the Wakulla River last weekend. For Teale—at least the character he plays in North With the Spring—nature was the substance within which life unfolded, inseparable from daily existence. For me, it is a commodity to be consumed. I engage the natural world fresh from the sporting goods store like a student joining the intramural league. The commodification of nature is nothing new, of course. David Nelson shows, for example, how the Civilian Conservation Corps and Florida business interests worked together to develop the modern tourism industry in the Florida Park System.

Still, I can’t help but think that the separation of human from nature is rapidly and irreversibly accelerating. Teale drove with the windows down because his car didn’t have an air conditioner. Would he drive with the windows up today, podcast blaring? He heard frogs and birds from the windows of Pullman coaches because that was how people traveled across the country at that time. Would he put on his headphones and watch a movie on the plane at 35,000 feet today? He woke to the sounds of boats and birds in the Ten Thousand Islands because open windows were the only way to cool the room. Today, like the rest of us, he would probably wake up to the roar of the air conditioner beneath the hotel window blowing ice cold air into the room.

These are things I don’t want to give up, but North With the Spring reminds me of the beautiful, natural things I have give up in exchange for comfort.