Call it a passion project. The past few days in my spare time at work I’ve been recovering data from twenty-five and thirty-year old floppy disks. The files on these old disks—CAD drawings, meeting minutes, reports, and other construction-related documents structured in 1.44 MB or smaller bundles—are interminably boring, but there is something intellectually thrilling in the process of accessing and reviewing them. I’ve been thinking of this as an archival thrill, similar in the little raised neurons it tickles to the feeling I get when chasing leads in old newspapers or digging through a box of original documents in search of names, clues, faces. Entire careers have come and gone since these files were copied to the magnetic circles in their little plastic cases. Whole computing paradigms have risen and fallen in that time, and, with them, our own sense of technical superiority to the people who authored these files. Still, the same meticulous attention to detail is evident in the files, the same sense of their own sophistication on the part of the authors, the same workaday problems we are solving today.

Working the files, I noticed two more things:

- The sound of a physical device reading data is special, and it can be deeply satisfying. I had forgotten the audible experience of computing—the whining, clicking, tapping, and whirring which used to characterize the entire experience. All of this is gone now, replaced by the sterile sound of fans, maybe, like wind blowing over a dried lakebed. There are audible affordances in physical media. When the sound stops, for example, the transfer is finished. When the button clicks on a cassette tape, the experience is complete.

- The old files on these disks are authored with maximum efficiency in mind. With only a few hundred KBs to work with, designers had to get creative in ways we don’t today. There are a lot of pointillistic graphics, tiny GIFS, plaintext, line drawings; none of the giant, full-resolution graphics we include everywhere today.

One of the disks contains a full website, preserved like a museum piece from 1999. Clicking around those old pages got me thinking about the archival thrill of the old internet.

Consider the way that the most prominent metaphors of the web have shifted over time.

It used to be that people would surf information on the internet, riding a flow state wave across documents and domains in pursuit of greater knowledge, entertaining tidbits, or occult truths previously hidden in books, microfilm, periodicals, letters, and other texts. The oceanic internet held out the sort of thrill you feel when wandering among the stacks of a vast library or perusing the Sufi bookstalls of old Timbuktu. It was an archival thrill, tinged with participatory mystique, abounding with secrets.

In the heady days of the early web, to surf was to thrill in the freedom of information itself.

When Google arrived on the scene and began its ongoing project of organizing the information on the web, feeding took the place of surfing. This act, like every triumph of industrial capital, relied first upon the extraction of surplus value from the laborers who produced the commodity—i.e., the authors of the information. That is a subject for another day. More to my point in today’s rumination, however, Google’s revolutionary commodification of the web also took advantage of the customer’s innate narcissism. You have specific and important information needs, Google says with its design language, which this text bar can satisfy.

Google delivered on this promise by surfing the web on behalf of searchers. To deploy another (very stretched) oceanic metaphor, Google turned surfers into consumers of tuna fish. Each search serves up a little can of tuna. Enter a term in the box and out pops a little tin; pop the can and get what you need, increasingly on the first page; and then get on with Your Busy Life.

The Your Busy Life warrant is the play on narcissism. You don’t have time to surf, it says, because you are important. Have this can of tuna instead.

I love tuna. I search every day. Google was so successful, however, that the web wrapped itself around the tuna-dispensing search box. By the mid-2000s, users no longer used search primarily as an entry point to the waves but, rather, as a sort of information vending machine serving up content from Google’s trusted searches.

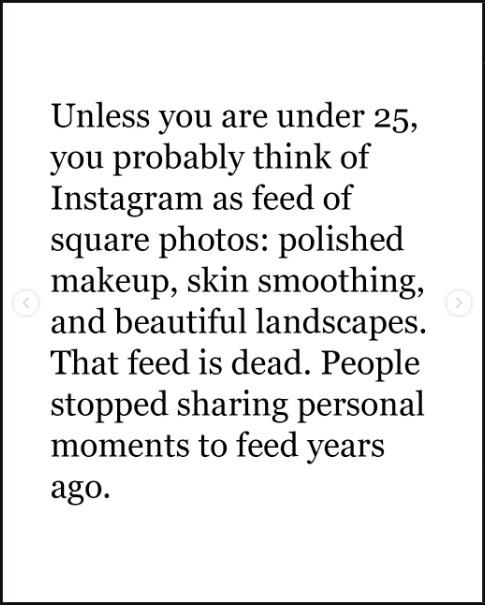

Beginning around 2008, feeding completely overtook surfing as the dominant user metaphor of the web. As Infinite-scroll apps on smartphones took the place of websites, the purveyors of these apps took it upon themselves to predict what users would like to know, see, or do. To this end, the most talented software engineers in the world have spent more than two decades now building algorithms designed to settle users in a stationary location and serve them little morsels of information on an infinite conveyor belt. Cans of tuna became Kibbles and Bytes, piece by piece, scrolling past.

The participatory mystique, or archival thrill, as I have called it, has been almost completely displaced by this dull feedlot experience. I know that the old experience of the web exists alongside the new, that I could go surfing right now if the urge carried me away, but I lament that so many of the people who could be building more and better websites are building cans of tuna for the Google vending machine on the web or Kibbles and Bytes for the apps.

Think of what we could have.