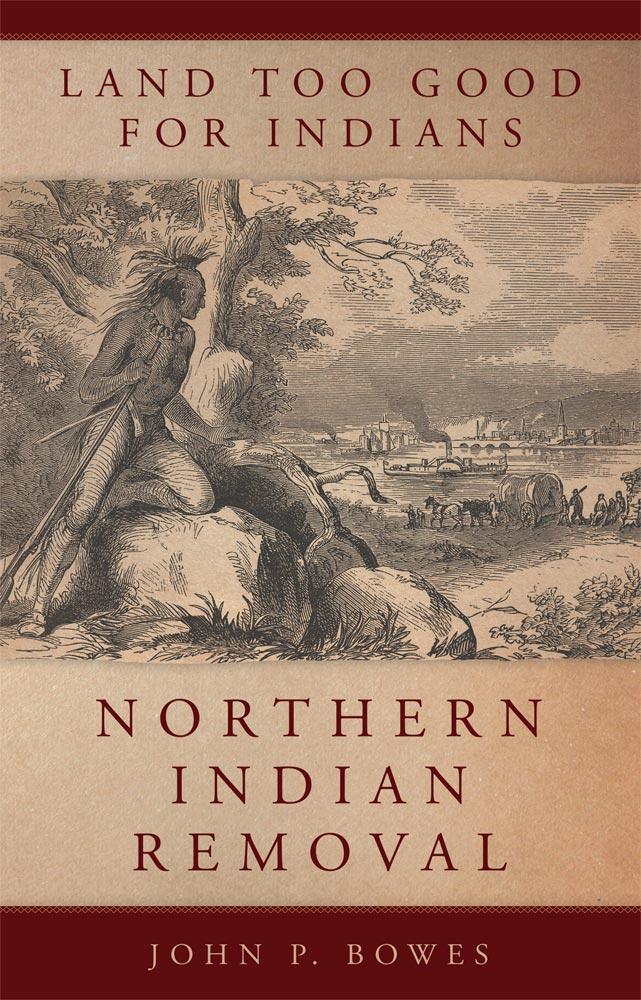

Bowes, John P. Land Too Good for Indians: Northern Indian Removal. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016. (Publisher link)

Though settler colonialism has thoroughly re-shaped Native American historiography in the past twenty years, scholars still tend to view Indian removal as a discrete moment or era in American history–a tragic narrative beginning with the transition from away from the Civilization plan marked by the passage of the Indian Removal Act by Congress in 1830 and culminating in the Cherokee Trail of Tears nearly a decade later. In Land Too Good for Indians, John P. Bowes argues that removal has instead been a central fact in the history of the American republic, rooted in the intertwining contexts of European colonialism and Native politics that preceded its founding, and enduring to the present. To advance this argument, Bowes examines the history of removal in the Old Northwest–the vast territory stretching from Ohio to eastern Minnesota. While many other scholars in recent years have studied the history of this region’s Native peoples, Bowes is the first in decades to take up the topic of removal for its own sake. In addition to shedding new light on removal in the North, Bowes along the way demonstrates the value of this kind of regional monograph in shaping the broader historiographical currents of settler colonialism and removal in the United States.

Bowes is sensitive to context in his definition of removal, arguing that the complicated process was shaped and mediated by the history of imperial violence in the region and the pervasive rhetoric of removal that accompanied this violence. The book’s two opening chapters explore these themes in depth. In the first, on violence, Bowes explores the imperial clashes that shaped the region before and immediately after the American Revolution, arguing that these conflicts contributed to a belief on the part of American settlers and policymakers that Indians were “savage agents of the British Empire” who could not abide peace [20]. This violence contributed to a rhetorical tradition that linked peace, propriety, and prosperity for Americans in the region with the removal of its Native peoples. American lawmakers responded to this rhetoric by crafting policies and embarking on a series of punishing wars that achieved removal–the subject of the book’s remaining chapters–while the history of violence and ongoing rhetoric of removal continue to leave deep scars on American Indians everywhere. Bowes closes the work with a chapter on the aftermath of removal and its legacy in memory, arguing that the “American era is a removal era.”

By shifting the terrain, Bowes offers a powerful corrective to the historiography of removal. While the scholarship of settler colonialism has thoroughly unsettled historians’ understanding of early America, there is still much work to be done “on the ground” to understand how settler colonialism as a foundational American political philosophy shaped the nation’s culture and politics. Looking away from the South, where scholarship on the history of capitalism and slavery continues to unearth new layers of meaning in the region’s Native history, forces scholars to re-evaluate the many contexts that shaped Indian policy. That said, some of the scholarship from other regions may have bolstered the theoretical framework that gives this book its shape. Engaging Matthew Jennings’ work on the clashing “cultures of violence” that shattered Native political power in the early American Southeast, for example, might have supported the chapter on violence–especially as we learn more about the myriad connections that drew (and continue to draw) Native peoples together across the continent. Likewise, Ned Blackhawk’s unique treatment of violence as a unit of analysis suggests intriguing possibilities for the argument about violence that forms such an important part of this book. The rhetoric of removal, too, seems an extension–an important and valuable expansion, to be sure–of Francis Jennings’ “cant of conquest.” These minor historiographical quibbles neither blunt the argument nor detract from the contribution this book makes to the historiography of removal and American settler colonialism, however, and scholars of Native history, the early republic, or the Old Northwest will find this book a valuable addition to their bookshelves for years to come.